This is not a joke. Today in the faculty room I discovered the secret to science teaching success. There on the front page of The International Educator’s monthly newspaper was an article celebrating a school presentation of a science show called Brainiac Live! In the presentation (which is based on a British television show) a guy who goes by the name Dr. Bunhead (not a joke either) lights his head on fire to inspire students about the wonders of science. So there you have it- being a great science teacher is simple. All you need to do is blow things up, create giant ballons, shoot lightning bolts out of your fingertips, but most importantly- light your head on fire!

This is not a joke. Today in the faculty room I discovered the secret to science teaching success. There on the front page of The International Educator’s monthly newspaper was an article celebrating a school presentation of a science show called Brainiac Live! In the presentation (which is based on a British television show) a guy who goes by the name Dr. Bunhead (not a joke either) lights his head on fire to inspire students about the wonders of science. So there you have it- being a great science teacher is simple. All you need to do is blow things up, create giant ballons, shoot lightning bolts out of your fingertips, but most importantly- light your head on fire!

I hope you notice a slight hint of sarcasm here. It actually seemed highly ironic that this newspaper which celebrates best practices in education would be highlighting something that I consider worst practice. Don’t get my drift? Read on…

Science shows like these are intended to get students excited about science, right? And there’s no question that they’re exciting- who doesn’t want to watch Dr. Bunhead nearly sear his scalp?? But what exactly are the students getting excited about? As teachers we would hope they’re getting excited about scientific ideas, scientific thinking, in short- excited about learning more science. But that’s not the case- instead students are only focused on the awesome scientific phenomenon in front of them (in this case Bunhead’s flaming head). They’re excited about the explosions, the noise, the surprising result, but not about the scientific explanation that usually comes afterwards.

Using a show like this to inspire your students in science is kind of like coaching your high school basketball team by showing them the NBA slam dunk contest. Are they going to be excited? Sure! Inspired? You bet- they can’t wait to start practice the next day and spend an hour on… dribbling drills. NOT! In fact it could be argued that this approach to coaching or teaching could even be detrimental- because kids will come to expect the flash-boom-bang and never develop an appreciation for the less obvious excitements that take place inside one’s own head (as opposed to in a fiery ball above it).

Example: Last week my 4th grade students were super pumped when they discovered by themselves how to create an electromagnet with a set of materials I gave them without further instruction. The fact that their simple electromagnets were so weak they could only lift up a few metal washers did not dampen their excitement one bit- because it wasn’t the phenomenon they were focused on, but the idea they had come up with. Imagine if instead I had started the lesson with a wow me demonstration of electromagnets- say lifting up a car with a giant electromagnetic crane and letting it come crashing down when I turned it off, and then follow that up with some lecture or reading about electromagnets or even a hands-on activity building a smaller model of the one I demonstrated. What would students remember a week later? Of course they could all recall in detail how Mr. Mitchell totaled a car, but very few of them would remember much of anything about the scientific explanation afterwards, or the version they made that paled in comparison. They’d be stuck on the awesome phenomenon, and the idea behind it would be merely a forgotten afterthought.

For all you literalists out there, I’m not advocating that demonstrations be banished from current teaching practice, I just think we need to be more thoughtful about how we use them and what they will cause students to think about. We need to go beyond “whoa!” and get to “why?”. Going back to my actual 4th grade electromagnets lesson (which I should say was based on the great FOSS unit Electricity and Magnetism), I did actually start out with a demonstration: I showed students a video clip of magician Jean Robert-Houdin’s famous “Light and Heavy Chest trick“. In the trick, Houdin secretly used a hidden electromagnet to attract the small chest to the floor so that a burly audience member couldn’t pick it up, then he turned off the electromagnet so it could be picked up easily by a child. After showing the video I didn’t try to explain the trick (that would get me kicked out of the Alliance!), instead I had students think about it themselves. As a class they were able to figure out that some sort of special magnet must be involved that could turn on and off- viola- electromagnets. I then told them they could use their knowledge about circuits to try and turn a steel rivet into a magnet that could be turned on and off, gave them the materials, and let them have at it. Using a demonstration in this way, as a teaser to introduce a problem/question/challenge, is in my opinion much more effective. (The parallels with narrative are striking- you would never start a story with a resolved climax, so why would you start your lesson with the most interesting part first?)

So go ahead and enjoy Dr. Bunhead’s pyrotechnics, just don’t expect this approach to inspire the next generation of scientists, or expect it to work well in the classroom. Students (and adults) are already amazed by fiery explosions, and a bunch of wow me science demonstrations are going to result in excitement about more fiery explosions, but not kindle much learning. Our real challenge as teachers is to figure out how to get students amazed by their own observations, their own thinking, to spark that fire in their mind- not on their head.

(Short disclaimer: I have not seen Dr. Bunhead’s particular science show, but I have seen others which I believe are very similar. Perhaps while Dr. Bunhead’s head burns down he also engage his large student audience in hands-on inquiry-based activities that inspire scientific thought and discovery… but I doubt it.)

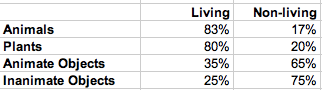

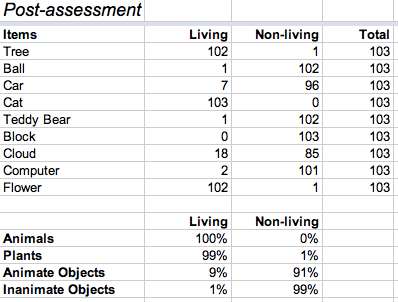

We just completed our Kindergarten unit about living and nonliving things. As with all our elementary science units, we collect pre and post assessment data, in order to get an overall idea of how well students learn the intended concepts. Of course the main idea of the unit is differentiating between living and nonliving things, so we focus our pre and post assessment on this skill with a simple paper and pencil activity:

We just completed our Kindergarten unit about living and nonliving things. As with all our elementary science units, we collect pre and post assessment data, in order to get an overall idea of how well students learn the intended concepts. Of course the main idea of the unit is differentiating between living and nonliving things, so we focus our pre and post assessment on this skill with a simple paper and pencil activity: